Since my first

posting on the sad news that

Stacey's Bookstore in San Francisco had announced it will be closing in March after 85 years in San Francisco, I've been following the story online and through friends in San Francisco. On Facebook I was encouraged to discover a "grassroots" effort organizing to "

Save Stacey's Bookstore." I've also heard from many people, online and off, expressing shock and dismay at the news. On behalf of Independent Booksellers everywhere, let me extend my thanks to all the good people out there who care about where they buy their books and from whom. What we do, and the opportunity to do it, depends on just such thoughtful, community-minded patrons. We have always been, and continue to be grateful for your support, and your business. And if I may still presume to speak for the booksellers at Stacey's, I'm sure they are just as grateful for the many new and familiar voices joining the chorus now rising to try to save that venerable bookstore.

In my reading online, I have also discovered just how many people there are out there who seem to misunderstand the nature of just what it is we do; assuming, for example, that the prices of the books we sell are a matter of choice for independent retailers, that discounts to customers and variety of selection are dictated exclusively, or even primarily by considerations of profit and promotion, and that even the continued viability of independent bookselling is ultimately more a matter of management and competition than it is a matter of cultural or community significance. Let me try, in my own unbusinesslike way, to address some of these points, as briefly and as well as I can in this space.

Without becoming too mired in the jargon of bookselling and publishing, let me just begin by suggesting that the whole business of books is, has always been, and Gods willing, will always be an irrational, impractical and frankly foolhardy enterprise. The suggestion that anyone can, or has, or ought to make a proper, well organized, smooth-running machine of Market Capitalism out of writing, printing, publishing or selling books, is as familiar, and touching to booksellers, however humble, as it is to anyone else who may have spent their lives in the service of books. Many a better man and woman of business than me has been broken on that wheel. Business, and in particular the business of books, has seen many an entrepreneur rise and fall in the tide of print. Many have made fortunes, or at least reputations as innovators and great capitalists from books, from the man who opened bookstalls in Victorian train-stations, to the popularizer of classics in paperback, to Jeff Bezos of Amazon.com. Each is to be well remembered and applauded for their contributions to the culture as well as for their business acumen and willingness to risk their own and other people's money in such, for the time, questionably profitable gambles. But for every innovator in publishing and selling, there have always been hundreds or possibly even thousands of less daring souls, readers and retailers, bibliophiles and buyers and tradesmen more like... well, me.

We no more set the price of a hardcover from Random House than we determine the value of Amazon.com stock. And we live, as do the independent publishers, the freelance writers, editors and translators, and, it would seem, the readers and collectors of less established, or well remembered authors, on the narrow margins of solvency, not because we are reckless or stupid or undisciplined, but because what we love is the company of books more perhaps than we do the business of books, and will, it seems, often as not, sacrifice, to our own ultimate ruin perhaps, the latter to secure the former.

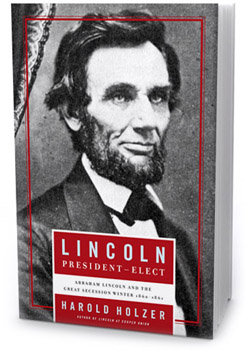

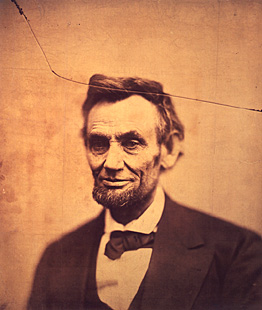

A short discounted title from an academic press on an obscure subject? But surely, Stacey's must have at least a copy of such a book on the shelf when, and if, the right customer comes in to find just such a book? Else how will the reader know he or she needs it? Not one, or even a few of the newest or the best books on Lincoln for the University Book Store, but all the titles we can get that might be worth having when we set up a display table to celebrate the Bicentennial of his birthday, else are we not doing a disservice to our customers and to the writers and scholars who have labored to preserve our history and his memory?

And if we can not discount the New York Times Bestsellers list as a result, or choose to promote our own selection instead... And if we can not sell every bestselling new children's title at prices to compete with Costco, but choose to celebrate the PNBA Lifetime Achievement Award winner Alexandra Day by carrying every available title in multiple copies instead...

That is the value that is lost in the passing of Stacey's. Those who criticize or sneer at the incompetence of the independent bookstore in the face of the more elegant and profitable business model of the chain store, or whose purchasing is dictated by the automated suggestions provided by the wizardry of online marketing, rather miss the point. We do not do this, and Stacey's did not do what they did for 85 years, because we, or they, hoped one day to be rich as the result of of our labour. We, and they, did and do consider ourselves rich in the books and authors we've known, the customers we've met, the generations whose reading and opinions we've cultivated and cared about, in the culture we've supported and sold. We simple booksellers, in all our enthusiasm and old-fashioned amateurism, have done what we do because we believe, ultimately, more in the supremacy of the word than the dollar.

And if that sounds too grand for such as us, perhaps it is. We are ultimately peddlers, not artists. But do please at least give us this: should Stacey's, and all like it, be allowed to go, do you really think the world will be a more art-full, or a better place? Or will it be, simply, a more profitable and convenient market? Nothing wrong with that, of course. As you like it.

Meanwhile, my thoughts and my heart go to Stacey's and all who still love the books, and the booksellers therein.

While this hardly mitigates the dustjacket design, seeing The Lincoln Anthology: Great Writers on His Life and Legacy from 1860 to Now, in a boxed set from Library of America, goes a long way to making me happier about trying to sell the book.

While this hardly mitigates the dustjacket design, seeing The Lincoln Anthology: Great Writers on His Life and Legacy from 1860 to Now, in a boxed set from Library of America, goes a long way to making me happier about trying to sell the book. I've been trying to get the two volumes of Speeches and Writings back into the store in time for the Bicentennial, but I hadn't had any luck. Now I understand why. Redesigned with red and blue covers, and boxed with the anthology, they make a handsome, if a little on-the-nose design for this bran new presentation.

I've been trying to get the two volumes of Speeches and Writings back into the store in time for the Bicentennial, but I hadn't had any luck. Now I understand why. Redesigned with red and blue covers, and boxed with the anthology, they make a handsome, if a little on-the-nose design for this bran new presentation.

I've only just begun White's book, but I am excited already at the prospect of hearing so eminent a scholar speak on the 16th President. His earlier work includes

I've only just begun White's book, but I am excited already at the prospect of hearing so eminent a scholar speak on the 16th President. His earlier work includes

.jpg) Periodically, C-SPAN gathers some of Lamb's "interviews," or friendly interrogations might be more apt, into a kind of a book. Now, they've gathered excerpts from C-SPAN many wonderful Lincoln broadcasts, Booknotes interviews and the like into a new book,

Periodically, C-SPAN gathers some of Lamb's "interviews," or friendly interrogations might be more apt, into a kind of a book. Now, they've gathered excerpts from C-SPAN many wonderful Lincoln broadcasts, Booknotes interviews and the like into a new book,  War: Ultimate Sticker Book, $2.98.

War: Ultimate Sticker Book, $2.98.

Father Abraham: Lincoln's Relentless Struggle to End Slavery, by Richard Striner. $9.98 in hardcover.

Father Abraham: Lincoln's Relentless Struggle to End Slavery, by Richard Striner. $9.98 in hardcover.

Now

Now